The state of affairs is pressing. In July of final yr, Panama declared a state of animal well being emergency amid outbreaks of cattle screwworm all through the nation. And this February, greater than 200 circumstances of screwworm assaults on animals have been reported in Costa Rica, prompting the federal government to declare an emergency as effectively. In Uruguay, screwworm flies value the livestock business $40 million to $154 million a yr. Agricultural export is the linchpin of Uruguay’s economic system—over 80% of the products the nation exports are agricultural merchandise. Beef, which accounts for 20% of that, is price $2.5 billion a yr.

That makes the nation’s seek for new instruments to fight the pests much more essential, says Carmine Paolo De Salvo, a rural growth knowledgeable on the IDB. “The [Uruguayan] authorities is beneath fixed strain to do one thing about it,” he says.

Scientists have been attempting to sort out screwworms for many years. One technique, often called the sterile insect method (SIT), was developed by researchers on the US Division of Agriculture within the Fifties. SIT entails sterilizing male screwworm flies with radiation. Then, utilizing airplanes, the DNA-damaged males are dropped on the realm of infestation. Once they mate with wild feminine flies, the eggs which can be produced don’t hatch, slowing inhabitants progress and stopping the unfold of the parasite.

That method has labored in lots of nations, together with components of Central America, liberating livestock and wildlife by the tens of millions from the painful grip of the pests. Within the US, an area-wide eradication program utilizing SIT labored so effectively that in 1966, the USDA declared screwworm eradicated inside the nation’s borders. The advantages to the livestock business have been immense: producers saved as much as $900 million, and the well being of each wild and livestock improved.

Even with sterile males, eradicating screwworms stays a cussed problem, nonetheless. To stop the screwworms from returning, the US—together with Central and South American nations—nonetheless runs a everlasting barrier zone of sterile flies on the Panama-Colombia border, requiring a steady provide of billions of flies yearly. This effort is just too costly, and it’s merely not highly effective sufficient to eradicate screwworm in South America, the place the pests are firmly established and troublesome to surveil, researchers say. So the search has been on for various instruments.

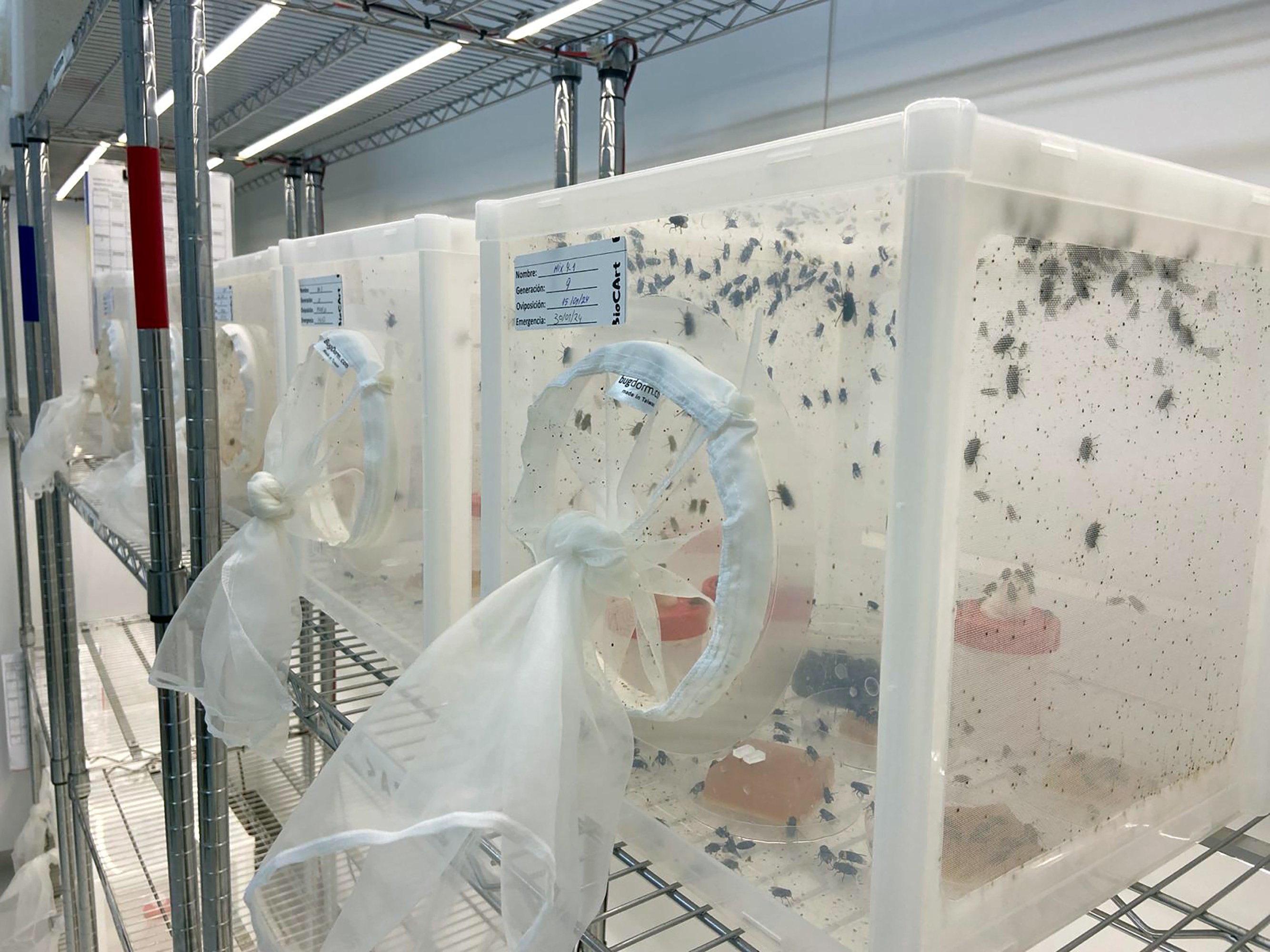

COURTESY OF ALEJO MENCHACA

It was Kevin Esvelt, a pioneering chief in CRISPR gene-drive techniques, who first turned the crew on to the concept of utilizing one. Esvelt had been experimenting with engineering localized variations of gene drives to focus on Lyme illness within the US when he met the crew of Uruguayan researchers on a tour of the MIT Media Lab. Shortly after that assembly, Esvelt was on a aircraft to Uruguay, the place he met Menchaca and satisfied Uruguayan officers to provoke a gene drive undertaking to eradicate screwworms. This could have the benefit over SIT as a result of whereas SIT reduces the variety of profitable births, the infertility conferred by the gene drive passes by means of a number of generations.

The crew is trying to make use of an method that Scott has efficiently developed for livestock pests. In a current examine, Scott and his crew examined it on the spotted-wing drosophila, an invasive fly that assaults soft-skinned fruit. The gene drive they developed for that examine carried an edited model of the so-called doublesex gene, which is important for the fly’s copy. In caged trials, they mixed the engineered fly inhabitants with a inhabitants that didn’t have the gene edits, mimicking a real-world launch. They discovered that the gene drive was copied at a price of 94% to 99%—past the effectivity they’d anticipated. “It was the primary actually efficient-homing gene drive for suppression of an agricultural pest,” says Scott. He hopes {that a} comparable method will work with screwworms and permit researchers to carry out safer exams.

It gained’t be a fast course of. Assembling the gene-drive system, testing it, and securing approvals for subject launch might take a few years, says Jackson Champer, a researcher at Peking College in Beijing, who isn’t a part of the Uruguayan crew. “It’s not a simple process; there have been many failed makes an attempt at gene drives.”