Intermittent fasting is an eating pattern where you alternate between periods of eating and forgoing food.

If that sounds stupid, uncomfortable, or unhealthy, I understand—I thought the same thing when I first heard about it years ago.

It surprised me to learn, however, that intermittent fasting can be an effective tool for improving dietary compliance. It has good science on its side, too, and it doesn’t have to be unpleasant.

In fact, many people, including thousands of those who’ve gotten amazing results using my books and body transformation coaching service, enjoy intermittent fasting more than traditional “dieting,” because it allows them to have fewer, larger meals.

That said, intermittent fasting isn’t some mystical key to optimal fitness and health. It won’t effortlessly transform your physique, evaporate belly fat, or halt the aging process.

What it can do is make your diet easier to follow and enhance your long-term results if you enjoy it.

That’s why you should understand what it is, how it works, and how to use it, which is exactly what you’ll learn in this article.

What Is Intermittent Fasting (IF)?

Intermittent fasting (or “IF”) is an eating pattern where you alternate between periods of eating and fasting.

While people often refer to intermittent fasting as a “diet,” it’s not entirely accurate to do so.

IF protocols usually don’t specify how many calories you should eat or the balance of macronutrients and types of food you should consume. Instead, they limit when you can eat, hence why calling it an “eating pattern” is more fitting.

Intermittent fasting has gained popularity in the health and fitness space because many believe it has significant health benefits, including weight loss, improved metabolic health, and possibly increased longevity.

How Does Fasting Work?

In a general sense, a “fast” is a period during which you abstain from eating (and sometimes drinking), often for religious reasons.

In the context of fitness, fasting isn’t just about not eating—it’s about how your body processes and absorbs food.

When you eat, your body breaks down the food into various molecules that enter your bloodstream. The hormone insulin then shuttles these molecules into cells.

When your body is digesting and absorbing what you’ve eaten, and insulin levels are still high, your body is in a fed or postprandial state (“prandial” means having to do with a meal).

Once your body finishes processing and absorbing the nutrients, insulin levels drop to a minimum (baseline) level, and your body enters a “fasted” or postabsorptive state.

The time it takes to reach this fasted state depends on the size and composition of your meal, but generally, you won’t be truly “fasting” until you haven’t consumed anything containing calories for at least six hours.

Popular Intermittent Fasting Protocols

There are various approaches to intermittent fasting, but all involve cycling between periods of eating and not eating.

During the fasting phases, you consume minimal or no food, though you can drink calorie-free drinks (water, herbal tea, or black coffee, for example).

The following are the most well-known IF methods:

The 16/8 Method

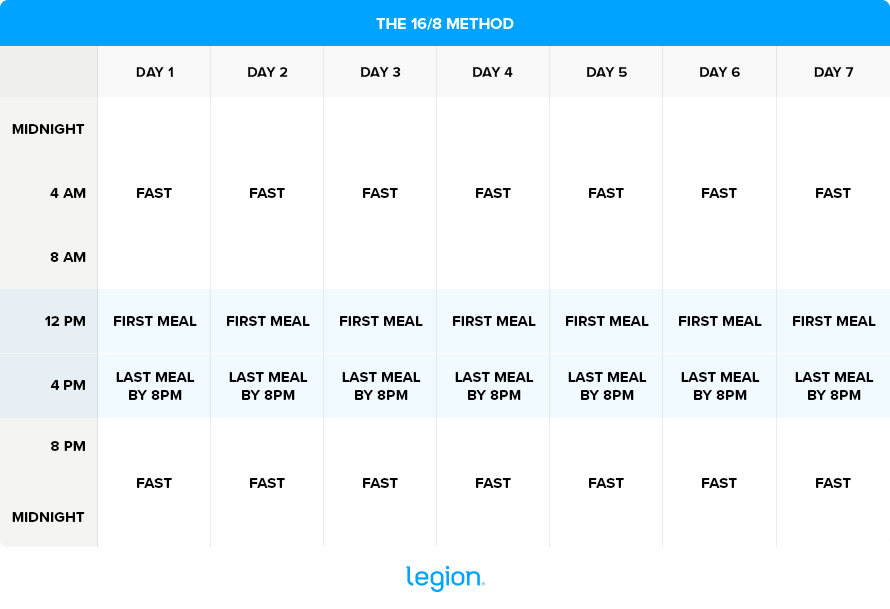

The 16/8 method is an intermittent fasting protocol where you fast for 16 hours per day and eat in an 8-hour window.

For most people, this means skipping breakfast and eating between lunch and dinner. For example, you might finish your dinner at 8 p.m., then not eat again until 12 p.m. the following day. Here’s how this would look across a week:

A noteworthy variation of the 16/8 protocol is Martin Berkhan’s “Leangains” method.

Like the 16/8 approach, the Leangains method has you eating all of your calories in an 8-hour window and fasting for 16 hours daily.

The difference is that the Leangains method includes more specific guidelines about macronutrient targets and meal timing (particularly around workouts) to maximize muscle gain.

Specifically, Leangains recommends the following:

- Workout Timing: Leangains suggests working out fasted, usually near the end of your fast, followed by the biggest meal of the day.

- Higher Protein: To maximize muscle growth, you eat a high-protein diet while following Leangains.

- Macronutrient Cycling: On Leangains you eat more carbs and calories on workout days versus rest days.

Based on my experience of helping thousands of people reach their health and fitness goals and my own dalliances with fasting, I’ve found the 16/8 (or Leangains) method to be the most practical fasting protocol for building muscle and losing fat.

The Warrior Diet

Ori Hofmekler popularized the Warrior Diet in his book of the same name.

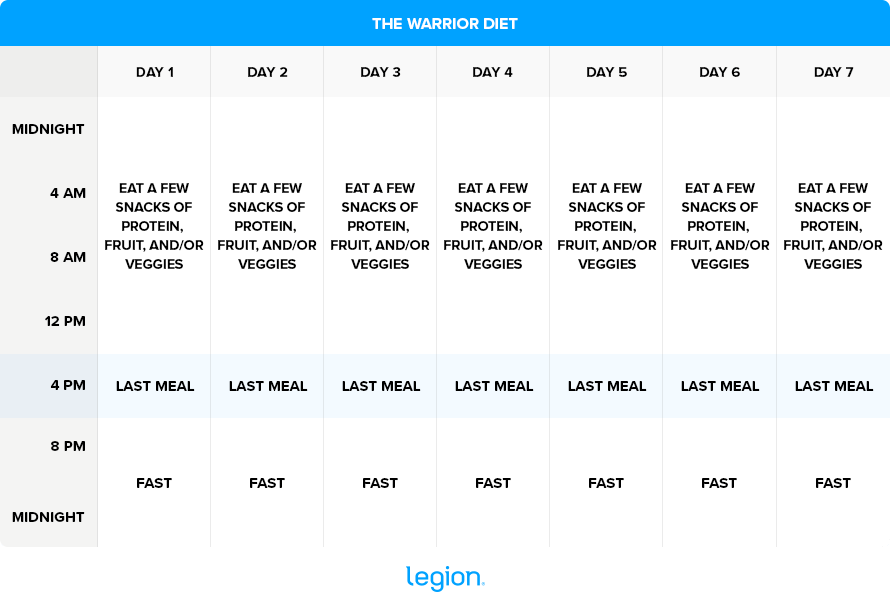

It involves eating one large evening meal in a 4-hour feeding window and then “fasting” for the remaining 20 hours each day.

I say “fasting” because you’re allowed to eat a few small snacks of protein, fruit, and/or veggies throughout the day, which will elevate insulin levels and break the fasted state.

Here’s how this looks across a week:

Furthermore, Hofmekler says you should start your big meal by eating vegetables, and then move to protein, and then fat. If you’re still hungry after eating fat, you can eat carbs.

The practical benefit of this is calorie control—you’re less likely to overeat this way versus starting your meal with a swan dive into a bowl of delicious carbs.

Generally speaking, I’m not a fan of the Warrior Diet.

While it can work for people who only like to eat once per day, most people find that it makes training difficult, managing hunger challenging, and consuming enough protein to maximize muscle growth almost impossible.

The 16/8 or Leangains method is almost always superior.

Alternate-Day Fasting

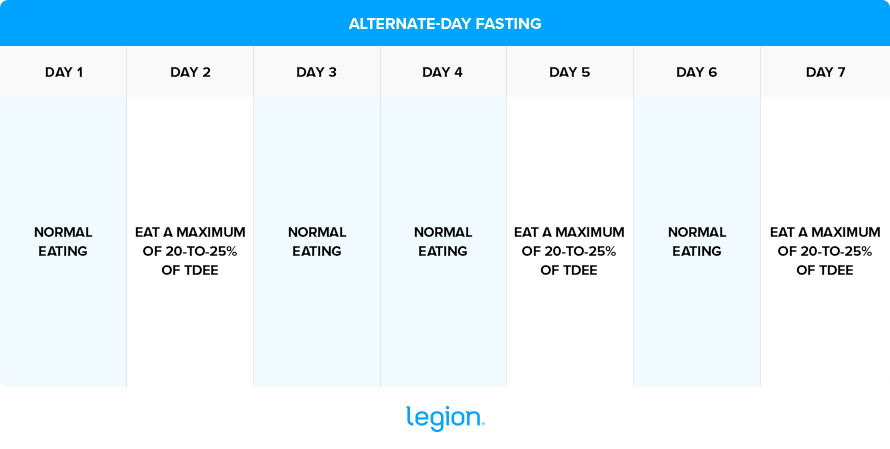

Alternate-Day Fasting (ADF) has you alternate between days of “normal” eating and “fasting.”

(Since a week has an odd number of days, alternating perfectly isn’t possible. Therefore, most people fast for 3 days and eat normally for 4 days each week.)

On “normal” days, you eat more or less the amount of energy you burn (TDEE). On “fasting” days, you eat 20-to-25% of this amount (around 500 calories for most people).

Here’s how it might look across a week:

From my experience, ADF is only suitable for very overweight sedentary people. When fit, active folks try it, their workouts usually suffer, which makes building muscle more challenging.

The 5:2 Diet

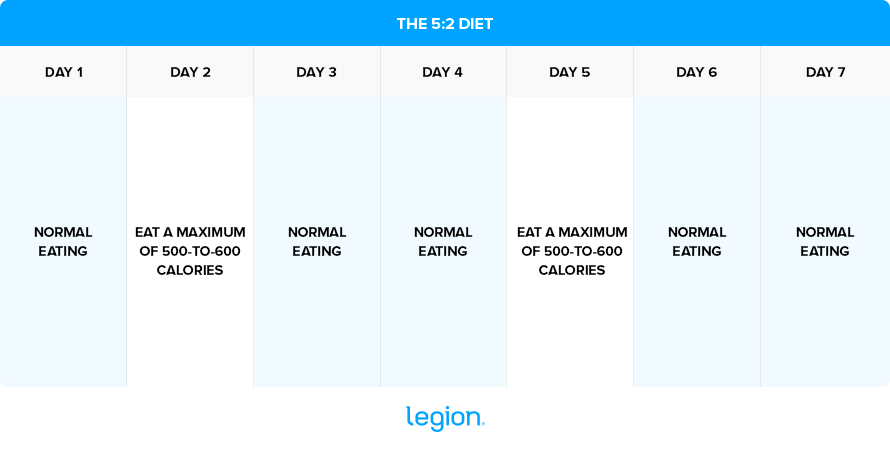

The 5:2 diet is similar to alternate-day fasting, only instead of fasting on 3 non-consecutive days per week, you fast on 2 non-consecutive days per week.

On your fasting days, you can eat a maximum of 500 calories if you’re a woman, and 600 calories if you’re a man.

Here’s an example of how to schedule it:

The 5:2 diet can work for people with a lot of weight to lose, but it can make training and eating a high-protein diet tougher, so it’s not ideal if you want to maximize muscle growth.

Eat Stop Eat

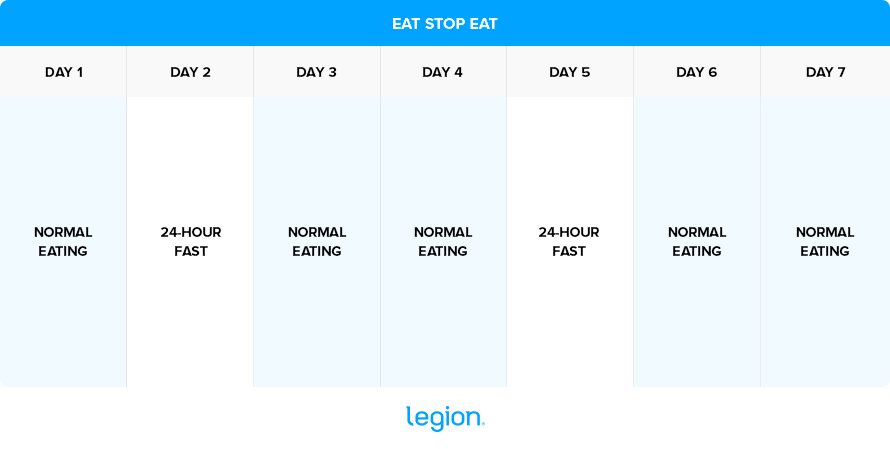

Eat Stop Eat is an intermittent fasting protocol created by Brad Pilon.

While following Eat Stop Eat:

- You fast for 24 hours once or twice per week on non-consecutive days.

- You can start your fasts when you like, but they must go for 24 hours. For instance, you could stop eating after your dinner one evening, then not eat again until the same time the following day. Or, if it suits your schedule better, you could finish your snack one afternoon, then fast until the same time the following afternoon.

Here’s how the Eat Stop Eat protocol looks for most people:

Unlike with most of the other popular fasting protocols that involve not eating for long periods, you can’t have any food during your fasting periods on Eat Stop Eat.

Because of this, the Eat Stop Eat method can be tough in the beginning. To make it easier, Pilon suggests the following:

- Start by fasting as long as you can and gradually work toward the full 24 hours.

- Start your fast while you’re busy and on a day where you have no social obligations that involve eating.

- Drink plenty of water

I typically don’t recommend Eat Stop Eat. The long fasts are uncomfortable for most people, and many find they succumb to binge eating when they’re finally allowed to eat, which can stymie weight loss.

Like other protocols involving long fasts, it also complicates training and high-protein dieting, which can hinder muscle gain.

Is Intermittent Fasting Better for Weight Loss than Traditional Dieting?

Research shows that most intermittent fasting protocols effectively help you lose fat, but this isn’t because fasting is inherently special for weight loss.

When studies compare IF diets to regular calorie-controlled diets, ensuring all the dieters eat the same number of calories and mix of macronutrients, people typically lose the same amount of fat regardless of their eating schedule.

The real reason IF can be a useful weight loss tool is that it helps some people create a calorie deficit more easily by limiting food intake to specific hours of the day or certain days of the week.

That said, not everyone enjoys fasting, especially over the long term. Studies show the more you have to change about how you eat—particularly how you like to eat—the more dietary compliance suffers and the worse your results will be.

Moreover, many people don’t take well to drastically reducing their meal frequency—they experience uncomfortable levels of hunger, irritability, and “brain fog.”

Research shows that fasting can encourage overeating by increasing the “reinforcing value of food,” too. Put differently, the more you abstain from eating (by fasting), the more value you can place on being able to eat, and this can cause you to eat more than you would otherwise.

Studies also show that fasting reduces the plasma levels of the amino acid tryptophan, which your body requires to produce serotonin (the “happy hormone”). As serotonin levels fall, many unwanted symptoms can arise, including depression, anxiety, sexual dysfunction, hyperactivity, digestive difficulties, food cravings, and more.

Another reason IF may not be suitable for everyone is that it can increase the risk of developing dysfunctional eating habits, particularly for those susceptible to disordered eating.

All that is to say, intermittent fasting isn’t a magic bullet for weight loss. It’s just a method of meal planning that can work well for people who prefer it over a traditional eating pattern.

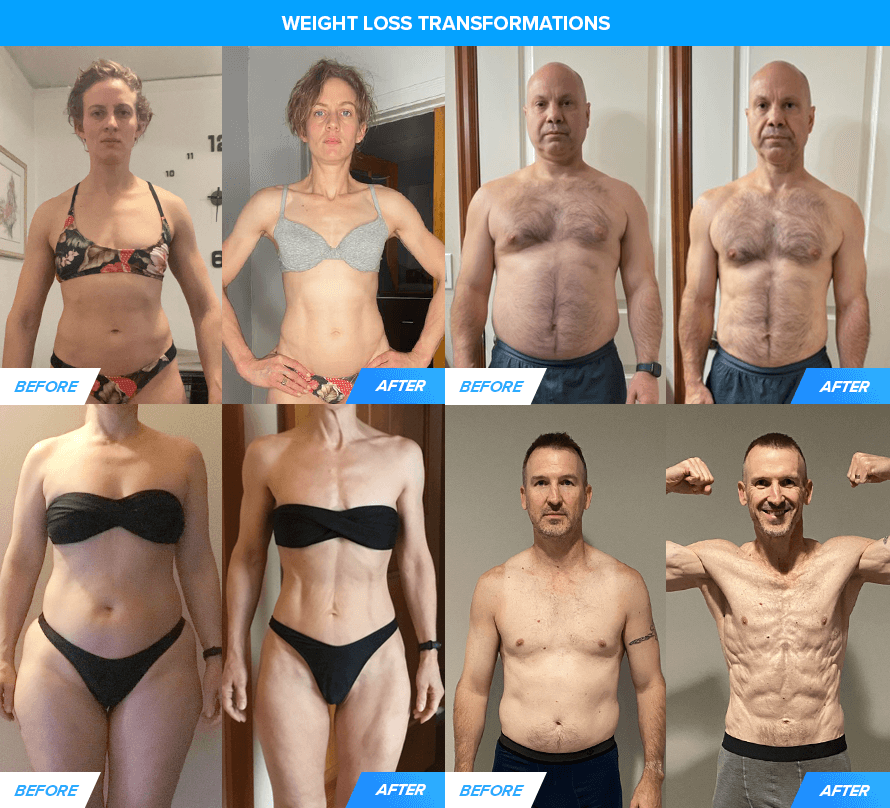

But you don’t need to fast to lose weight. A regular, calorie-controlled diet is just as effective and might better suit your preferences. For example, most people who join Legion’s body transformation coaching program choose a regular eating schedule, and there’s no shortage of “proof” it produces amazing results:

Is Intermittent Fasting Healthier Than Traditional Dieting?

Most claims relating to improved health while fasting focus on two points: blood glucose (sugar) control and autophagy.

Let’s look at each separately.

Blood Sugar Control

Fasting fans argue that eating several times a day “spikes” blood sugar too frequently, increasing levels of inflammation in your body and desensitizing your cells to insulin. Over time, this increases your odds of suffering health issues.

Their solution is to extend periods of not eating, thereby keeping blood sugar levels lower for longer.

However, this reasoning is flawed.

While eating does increase inflammatory markers in your blood for a short while, these markers don’t stay elevated long enough to cause harm.

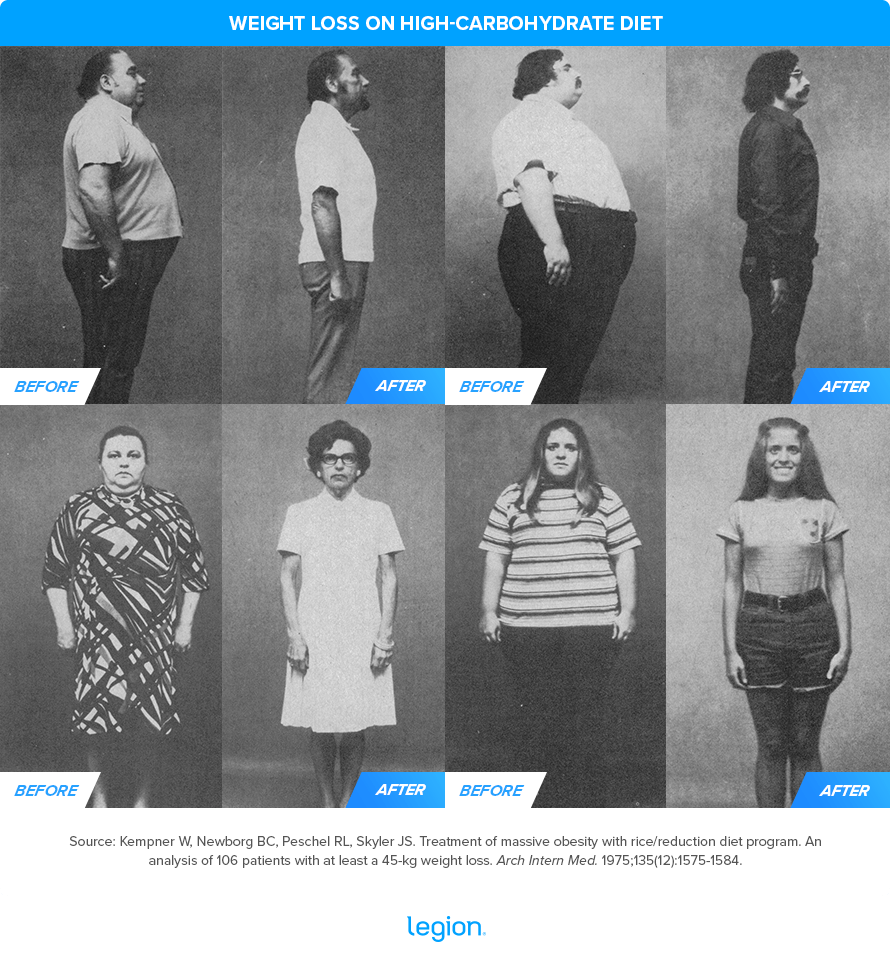

An elegant example of this comes from a study published in 1975 in the Journal Archives of Internal Medicine in which researchers had obese men and women eat in a large calorie deficit for more than a year, getting 90-to-95% of their daily calories from carbs (mainly white rice).

Despite the huge spikes in blood sugar, insulin, and inflammatory markers these dieters undoubtedly experienced after every meal, all of their health metrics (cholesterol, blood pressure, fasting glucose levels, and so forth) dramatically improved across the course of the study.

In other words, the short-term spikes in inflammatory nasties didn’t harm their long-term health. On the contrary, their health greatly improved because they lost fat. And boy did they lose fat:

This study underscores a crucial point: the overall effect of diet on body composition trumps the impact of temporary blood sugar fluctuations. That is, the end result of your diet (weight loss) matters more than the short-term effects of individual meals

Exercise is another good example of how short-term effects don’t always predict long-term outcomes.

When you lift weights, many measures of poor health, including increased inflammation, heart rate, and blood pressure, temporarily spike. Yet, people who exercise regularly are usually healthier and live longer than those who don’t.

Another reason to doubt fasting zealots’ claims about blood sugar control is that although eating fewer meals per day causes less frequent spikes in blood sugar, fasters tend to consume more when they eventually eat than people who have a regular meal schedule.

The result is that while fasters experience fewer small, short-term blood sugar spikes per day, they cause much larger, longer-lasting spikes when they finally eat. And that’s why research shows that the overall impact—the “area under the curve”—is similar no matter how you space out your meals, assuming you eat the same number of calories.

This isn’t to say that fasting can’t help improve blood sugar control—several studies show it can if it helps you lose weight. But there’s no evidence fasting is superior to regular calorie-controlled dieting for this purpose.

So, if you’re dieting to take control of your blood sugar, there’s no need to fast—follow whichever eating pattern makes losing weight most straightforward.

Autophagy

The term autophagy comes from the Greek for “self-eating” and refers to the body’s process of cleaning out damaged cells and recycling their components to keep cells functioning properly.

Think of it as a cellular housekeeping service, where the body clears away debris and repurposes broken or unnecessary parts to ensure everything runs smoothly.

Diet “gurus” often claim that fasting uniquely triggers autophagy, which, they say, helps combat aging and promotes longevity.

In reality, autophagy increases whenever you’re in a calorie deficit. IF helps some people maintain a calorie deficit, so it can also effectively increase autophagy. But, there’s nothing special about IF in this regard—maintaining a calorie deficit by any means will have the same effect.

That is, a regular, calorie-controlled diet triggers autophagy just as well as IF.

Still, some IF fanatics claim there’s evidence that fasting specifically increases longevity.

Crucially, this evidence comes from rodent studies. While rodent studies can sometimes provide insights into human biology, they’re not particularly useful for studying human longevity, primarily because rodents have much shorter lifespans, so a 16-hour fast for them equates to weeks or months for humans.

So, if you’re fasting for its supposed longevity benefits, you may want to reconsider. Losing weight and maintaining a healthy body composition—whether through IF or regular calorie restriction—is the real ticket to a longer, healthier life.

(Oh, and there’s plenty of research showing that exercise also increases autophagy, so if you want to boost longevity and you’re not already lifting weights, it’s high time you started.)

Does Intermittent Fasting Cause Muscle Loss & Hinder Muscle Growth?

Two common concerns about IF are that it causes muscle loss and hinders muscle growth.

The logic is simple: ordinary dieting allows you to eat protein at regular intervals, which keeps muscle protein synthesis (MPS) rates elevated throughout the day, theoretically keeping your “muscle-building machinery” firing.

In contrast, IF involves extended periods without food, during which MPS rates decline.

Over time, this might make it harder to build muscle and could lead to muscle loss, or so the theory goes.

Research challenges this line of thinking, though.

Two reviews comparing various IF protocols found no significant difference in muscle growth or retention between IF and regular dieting when dieters consumed sufficient protein. This suggests that IF probably doesn’t hinder muscle growth or cause muscle loss as long as you eat a high-protein diet.

Another noteworthy study published in Obesity (Silver Spring) split 18 overweight or obese men into two groups: a regular-diet group and an intermittent-fasting group.

Both groups maintained a calorie deficit, but the IF group ate within an eight-hour window, while the regular-diet group had a 12-hour feeding window.

The results showed that the IF group lost significantly more muscle (~2.2 lb) compared to the regular-diet group (~0.4 lb).

This seems concerning, but it’s probably less of an issue than it appears since the dieters neither lifted weights nor consumed adequate protein.

Thus, the real takeaway is that IF can lead to muscle loss if you don’t manage it properly. But given the other data we’ve seen, it’s probably not a significant issue for those who combine IF with regular strength training and a high-protein diet.

Many people believe that going too long without food triggers “starvation mode,” a state in which your body thinks it’s starving and rapidly stores fat when you finally eat.

This is a myth.

In one study, basal metabolic rate (BMR) didn’t decline until 60 hours of fasting, and the reduction was just 8%. In other words, if your BMR is 1,800 calories, it may drop to around 1,650 calories once you forgo food for 2 and a half days.

Other research shows that the metabolism actually speeds up after 36-to-48 hours of fasting. Although this seems counterintuitive, it makes sense from an evolutionary perspective.

If you haven’t eaten in a while, your body wants you to find food. To motivate you, it floods you with adrenaline and noradrenaline, sharpening your mind and, incidentally, increasing your metabolic rate.

The real “starvation mode” begins after about 72 hours of not eating, when muscle becomes the body’s primary energy source. Even then, the body takes measures to preserve muscle because of its vital role in keeping us strong, functional, and resistant to disease.

So, don’t worry about fasting ruining your metabolism. No sensible intermittent fasting protocol—like the ones we’ve discussed—will harm it.

+ Scientific References

- Surina, D. M., et al. “Meal Composition Affects Postprandial Fatty Acid Oxidation.” American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, vol. 264, no. 6, 1 June 1993, pp. R1065–R1070, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.6.r1065.

- Seimon, Radhika V., et al. “Do Intermittent Diets Provide Physiological Benefits over Continuous Diets for Weight Loss? A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials.” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, vol. 418, Dec. 2015, pp. 153–172, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2015.09.014.

- Maruthur, Nisa M, et al. “Effect of Isocaloric, Time-Restricted Eating on Body Weight in Adults with Obesity.” Annals of Internal Medicine, 19 Apr. 2024, https://doi.org/10.7326/m23-3132. Accessed 26 Apr. 2024.

- Templeman, Iain, et al. “A Randomized Controlled Trial to Isolate the Effects of Fasting and Energy Restriction on Weight Loss and Metabolic Health in Lean Adults.” Science Translational Medicine, vol. 13, no. 598, 16 June 2021, stm.sciencemag.org/content/13/598/eabd8034, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abd8034.

- Thomas, Elizabeth A., et al. “Early Time‐Restricted Eating Compared with Daily Caloric Restriction: A Randomized Trial in Adults with Obesity.” Obesity, vol. 30, no. 5, 26 Apr. 2022, pp. 1027–1038, https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23420. Accessed 1 July 2022.

- Liu, Deying, et al. “Calorie Restriction with or without Time-Restricted Eating in Weight Loss.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 386, no. 16, 21 Apr. 2022, pp. 1495–1504, https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2114833.

- Varady, Krista A., et al. “Cardiometabolic Benefits of Intermittent Fasting.” Annual Review of Nutrition, vol. 41, no. 1, 11 Oct. 2021, pp. 333–361, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-052020-041327.

- Cook, Florence , et al. Compliance of Participants Undergoing a “5-2” Intermittent Fasting Diet and Impact on Body Weight. 17 Aug. 2022, pp. P257-261, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2022.08.012.

- Schübel, Ruth, et al. “Effects of Intermittent and Continuous Calorie Restriction on Body Weight and Metabolism over 50 Wk: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 108, no. 5, 1 Nov. 2018, pp. 933–945, academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/108/5/933/5201451, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy196.

- Gibson, Alice, and Amanda Sainsbury. “Strategies to Improve Adherence to Dietary Weight Loss Interventions in Research and Real-World Settings.” Behavioral Sciences, vol. 7, no. 4, 11 July 2017, p. 44, www.mdpi.com/2076-328X/7/3/44, https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7030044.

- Epstein, Leonard H, et al. “Effects of Deprivation on Hedonics and Reinforcing Value of Food.” Physiology & Behavior, vol. 78, no. 2, Feb. 2003, pp. 221–227, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00978-2. Accessed 26 Aug. 2020.

- Cowen, P. J., et al. “Moderate Dieting Causes 5-HT 2C Receptor Supersensitivity.” Psychological Medicine, vol. 26, no. 6, Nov. 1996, pp. 1155–1159, https://doi.org/10.1017/s003329170003587x. Accessed 9 Nov. 2021.

- Stice, Eric, et al. “Fasting Increases Risk for Onset of Binge Eating and Bulimic Pathology: A 5-Year Prospective Study.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, vol. 117, no. 4, 2008, pp. 941–946, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2850570/, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013644.

- Gregersen, S., et al. “Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Responses to High-Carbohydrate and High-Fat Meals in Healthy Humans.” Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, vol. 2012, 2012, pp. 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/238056. Accessed 5 Apr. 2019.

- Erridge, Clett, et al. “A High-Fat Meal Induces Low-Grade Endotoxemia: Evidence of a Novel Mechanism of Postprandial Inflammation.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 86, no. 5, 1 Nov. 2007, pp. 1286–1292, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1286. Accessed 23 Mar. 2020.

- Kempner, W., et al. “Treatment of Massive Obesity with Rice/Reduction Diet Program. An Analysis of 106 Patients with at Least a 45-Kg Weight Loss.” Archives of Internal Medicine, vol. 135, no. 12, 1 Dec. 1975, pp. 1575–1584, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1200726/.

- da Luz Scheffer, Débora, and Alexandra Latini. “Exercise-Induced Immune System Response: Anti-Inflammatory Status on Peripheral and Central Organs.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. Molecular Basis of Disease, vol. 1866, no. 10, 29 Apr. 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7188661/, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165823.

- Nystoriak, Matthew A., and Aruni Bhatnagar. “Cardiovascular Effects and Benefits of Exercise.” Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, vol. 5, no. 135, 28 Sept. 2018. National Library of Medicine, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6172294/, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2018.00135.

- Carpio-Rivera, Elizabeth, et al. “Acute Effects of Exercise on Blood Pressure: A Meta-Analytic Investigation.” Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia, vol. 106, no. 5, 2016, https://doi.org/10.5935/abc.20160064.

- Zaman, Adnin, et al. “The Effects of Early Time Restricted Eating plus Daily Caloric Restriction Compared to Daily Caloric Restriction Alone on Continuous Glucose Levels.” Obesity Science & Practice, 4 Aug. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1002/osp4.702. Accessed 26 Feb. 2024.

- Corley, B. T., et al. “Intermittent Fasting in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and the Risk of Hypoglycaemia: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Diabetic Medicine, vol. 35, no. 5, 27 Feb. 2018, pp. 588–594, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/dme.13595, https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13595.

- Harvie, Michelle, et al. “The Effect of Intermittent Energy and Carbohydrate Restriction v. Daily Energy Restriction on Weight Loss and Metabolic Disease Risk Markers in Overweight Women.” British Journal of Nutrition, vol. 110, no. 8, 16 Apr. 2013, pp. 1534–1547, www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-nutrition/article/effect-of-intermittent-energy-and-carbohydrate-restriction-v-daily-energy-restriction-on-weight-loss-and-metabolic-disease-risk-markers-in-overweight-women/BC03063A5D8E9446D5090DB083A4B226, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114513000792.

- Harvie, M N, et al. “The Effects of Intermittent or Continuous Energy Restriction on Weight Loss and Metabolic Disease Risk Markers: A Randomized Trial in Young Overweight Women.” International Journal of Obesity, vol. 35, no. 5, 5 Oct. 2010, pp. 714–727, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3017674/, https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.171.

- Carter, Sharayah, et al. “Effect of Intermittent Compared with Continuous Energy Restricted Diet on Glycemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes.” JAMA Network Open, vol. 1, no. 3, 20 July 2018, p. e180756, jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2688344, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0756.

- Carter, S., et al. “The Effects of Intermittent Compared to Continuous Energy Restriction on Glycaemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes; a Pragmatic Pilot Trial.” Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, vol. 122, Dec. 2016, pp. 106–112, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2016.10.010.

- Carter, S., et al. “The Effect of Intermittent Compared with Continuous Energy Restriction on Glycaemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: 24-Month Follow-up of a Randomised Noninferiority Trial.” Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, vol. 151, May 2019, pp. 11–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2019.03.022.

- Bergamini, Ettore, et al. “The Role of Autophagy in Aging: Its Essential Part in the Anti-Aging Mechanism of Caloric Restriction.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1114, 1 Oct. 2007, pp. 69–78, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17934054, https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1396.020. Accessed 30 Apr. 2020.

- Shabkhizan, Roya, et al. “The Beneficial and Adverse Effects of Autophagic Response to Caloric Restriction and Fasting.” Advances in Nutrition, vol. 14, no. 5, 30 July 2023, pp. 1211–1225, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10509423/, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advnut.2023.07.006.

- Bagherniya, Mohammad, et al. “The Effect of Fasting or Calorie Restriction on Autophagy Induction: A Review of the Literature.” Ageing Research Reviews, vol. 47, Nov. 2018, pp. 183–197, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2018.08.004.

- Yang, Yi, and Lihui Zhang. “The Effects of Caloric Restriction and Its Mimetics in Alzheimer’s Disease through Autophagy Pathways.” Food & Function, vol. 11, no. 2, 2020, pp. 1211–1224, https://doi.org/10.1039/c9fo02611h. Accessed 11 May 2020.

- Pak, Heidi H., et al. “Fasting Drives the Metabolic, Molecular and Geroprotective Effects of a Calorie-Restricted Diet in Mice.” Nature Metabolism, vol. 3, no. 10, 1 Oct. 2021, pp. 1327–1341, www.nature.com/articles/s42255-021-00466-9#:~:text=Our%20results%20shed%20new%20light, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-021-00466-9. Accessed 6 Jan. 2022.

- J. Mitchell, Sarah , et al. Daily Fasting Improves Health and Survival in Male Mice Independent of Diet Composition and Calories. 18 Sept. 2018, pp. P221-228.E3, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.08.011.

- Brandhorst, Sebastian , et al. A Periodic Diet That Mimics Fasting Promotes Multi-System Regeneration, Enhanced Cognitive Performance, and Healthspan. 18 June 2015, pp. P86-99, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.012.

- Botella, Javier, et al. “Exercise and Training Regulation of Autophagy Markers in Human and Rat Skeletal Muscle.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 23, no. 5, 27 Feb. 2022, p. 2619, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23052619. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

- Brandt, Nina, et al. “Exercise and Exercise Training‐Induced Increase in Autophagy Markers in Human Skeletal Muscle.” Physiological Reports, vol. 6, no. 7, 6 Apr. 2018, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5889490/, https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.13651. Accessed 31 May 2021.

- Escobar, Kurt A., et al. “Autophagy and Aging: Maintaining the Proteome through Exercise and Caloric Restriction.” Aging Cell, vol. 18, no. 1, 15 Nov. 2018, p. e12876, https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.12876. Accessed 28 Feb. 2020.

- Conde-Pipó, Javier, et al. “Intermittent Fasting: Does It Affect Sports Performance? A Systematic Review.” Nutrients, vol. 16, no. 1, 4 Jan. 2024, pp. 168–168, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10780856/, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010168.

- Parr, Evelyn B, et al. “Eight‐Hour Time‐Restricted Eating Does Not Lower Daily Myofibrillar Protein Synthesis Rates: A Randomized Control Trial.” Obesity, vol. 31, no. S1, 22 Dec. 2022, pp. 116–126, https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23637. Accessed 30 Aug. 2023.

- Nair, K S, et al. “Leucine, Glucose, and Energy Metabolism after 3 Days of Fasting in Healthy Human Subjects.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 46, no. 4, 1 Oct. 1987, pp. 557–562, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3661473-leucine-glucose-and-energy-metabolism-after-3-days-of-fasting-in-healthy-human-subjects/, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/46.4.557. Accessed 22 Dec. 2019.

- Zauner, C, et al. “Resting Energy Expenditure in Short-Term Starvation Is Increased as a Result of an Increase in Serum Norepinephrine.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 71, no. 6, 2000, pp. 1511–5, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10837292, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1511.

- E Owen, Oliver , et al. Protein, Fat, and Carbohydrate Requirements during Starvation: Anaplerosis and Cataplerosis. July 1998, pp. P12-34, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/68.1.12.

- Lee, Christine G., et al. “Mortality Risk in Older Men Associated with Changes in Weight, Lean Mass, and Fat Mass.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 59, no. 2, Feb. 2011, pp. 233–240, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03245.x. Accessed 5 Mar. 2021.